We enter yet another interesting week in Europe with the same discussions on how high interest rates will be in Italy or Spain, rumors on a possible IMF program for Italy (doubtful) and pressures on the ECB to do more. So far ECB officials argue that "bailing out" Euro governments will violate their legal framework and it is a bad idea. Without going again into the arguments of whether the ECB can and should buy Euro government debt, here is a quick comparison between the US Fed and the ECB in terms of holdings of government debt.

The chart below measures the holding of US government debt at the US Fed and Euro government debt at the ECB. They are measured in billions of local currency (USD for the US, EUR for the ECB).

If you look carefully at the last months you see a small increase in the ECB holdings that reflect their recent attempts to bring some stability to financial markets and keep bond yields under control. But how does it compare to the US Fed actions over the last two years?

Let's first compare the end point. Today the US Fed holds about 1.7 trillion of US government debt. This represents about 11% of the 15 trillion of outstanding US government debt. For the ECB, the holdings of government debt are about 550 billion (EUR), which is less than 7% of the total outstanding debt of Euro governments (around 8.3 Trillion).

If we look at the evolution over the last years we can see that from mid-2009 the US Fed has doubled the holdings of government debt. If we use 2008 as the starting point then we are looking at an increase of more than 300%. The decrease in holdings of government debt in the years 2008-09 corresponds to the period when the Fed was exchanging treasury bills against other assets such as MBS.

The ECB has also been increasing its holdings of government debt. From 2008 to today it has increased its holdings by about 66%. But this increase is not that different from the previous trend and there seems to be very little change during the crisis except in the last months.

The actions of the Federal Reserve are part of its monetary policy strategy and not an attempt to provide a hidden bailout to the US government (not everyone agrees on this but let's leave that discussion for the future). The comparison between the two central banks and the fact that the ECB is so reluctant to consider a similar action in the current environment where financial and macroeconomic stability are at risk makes the ECB decision even more difficult to understand.

Antonio Fatás

Monday, November 28, 2011

Friday, November 25, 2011

Ratings deflation: a world without AAA bonds?

First it was Greece, then Portugal, Ireland, Spain, Italy and France and Germany are maybe coming next. It seems that soon there will be no Euro countries left with AAA rating. Japan lost it a while ago and the US could follow when the next super-committee does not agree on what to cut or which taxes to increase. What happens if all countries lose their AAA-rating?

We know that in some cases we know that the impact of going down in the ratings is minimal - as it has been in the case of Japan where the government keeps funding very large deficits at low interest rates.

But what is more interesting, given current circumstances, is whether the rating can be seen as an absolute measure of the probability of default or a relative one. If you check what agencies say, they will not give you a definite answer to this question.

To the question "Are Credit Ratings absolute measures of default probability?", Standard and Poor's answers:

So if ratings are relative and they are all going down (deflation has also reached rating agencies), it might not matter much for investors. This might be a signal that the world is more volatile than what we thought, and this is not good news, but as long as nothing else look safer than these bonds, it might not change much the portfolio strategy of investors.

There is however a risk: that investors seek safe returns somewhere else. This happened to some extent in the period 2003-2007 where investors looked for returns in assets other than government bonds because of their low yields. And financial markets were very good at creating assets that offered higher returns and that apparently where as safe as government bonds. But we know that this story did not end very well.

We can imagine going forward a world where investors move away from government bonds not so much because of low yields but because of the perception of risk, and theysearch for yield in assets that appear less volatile or where the expected return more than compensates for the potential risk. We have seen this behavior in the gold market, the exchange rate market (with the Swiss Franc until the central bank said enough). But if deflation in ratings continues it is very likely that we will see similar phenomena in many other markets.

Antonio Fatás

We know that in some cases we know that the impact of going down in the ratings is minimal - as it has been in the case of Japan where the government keeps funding very large deficits at low interest rates.

But what is more interesting, given current circumstances, is whether the rating can be seen as an absolute measure of the probability of default or a relative one. If you check what agencies say, they will not give you a definite answer to this question.

To the question "Are Credit Ratings absolute measures of default probability?", Standard and Poor's answers:

"Since there are future events and developments that cannot be foreseen, the assignment of credit ratings is not an exact science. For this reason, Standard & Poor’s ratings opinions are not intended as guarantees of credit quality or as exact measures of the probability that a particular issuer or particular debt issue will default."Which is not too informative. And then they add:

"For example, a corporate bond that is rated ‘AA’ is viewed by Standard & Poor’s as having a higher credit quality than a corporate bond with a ‘BBB’ rating. But the ‘AA’ rating isn’t a guarantee that it will not default, only that, in our opinion, it is less likely to default than the ‘BBB’ bond."This is more informative but not much of a surprise: One would hope that at least the relative ranking of ratings says something about the relative default risk.

So if ratings are relative and they are all going down (deflation has also reached rating agencies), it might not matter much for investors. This might be a signal that the world is more volatile than what we thought, and this is not good news, but as long as nothing else look safer than these bonds, it might not change much the portfolio strategy of investors.

There is however a risk: that investors seek safe returns somewhere else. This happened to some extent in the period 2003-2007 where investors looked for returns in assets other than government bonds because of their low yields. And financial markets were very good at creating assets that offered higher returns and that apparently where as safe as government bonds. But we know that this story did not end very well.

We can imagine going forward a world where investors move away from government bonds not so much because of low yields but because of the perception of risk, and theysearch for yield in assets that appear less volatile or where the expected return more than compensates for the potential risk. We have seen this behavior in the gold market, the exchange rate market (with the Swiss Franc until the central bank said enough). But if deflation in ratings continues it is very likely that we will see similar phenomena in many other markets.

Antonio Fatás

Monday, November 21, 2011

Solvency or Liquidity? (r-g)

As we continue seeing interest rate spreads increasing in the Euro area, we keep asking the question of whether this is a crisis of solvency or liquidity. The fact that interest rates keep increasing makes it more difficult for governments to meet interest payments, and solvency becomes more likely. If default happens we might never find out what type of crisis we had. Were governments insolvent? Or did the high interest rates and lack of funding pushed them into default? And if we cannot tell ex-post, how can we tell ex-ante (now!)?

Let me look at some historical facts to understand the potential scenarios these countries are facing. After my previous post on Italy, let me look at Spain today, one of the countries that is also seeing spreads rapidly increasing.

The way we normally look at the question of solvency is by asking what type of effort the government needs to do to keep the debt under control. The typical benchmark is to look at the current ratio of government debt to GDP and think of scenarios where this ratio remains constant. In the case of Spain, this ratio is 60-67% measured in gross terms and 48-56% in net terms. The range corresponds to the number for 2010 and the forecast by the end of 2011. Let's just use 65% as the relevant ratio.

To keep this ratio constant, the Spanish government has to deliver a primary balance which is equal to the difference between the interest rate it pays on the debt (r) and the growth rate of GDP (g) multiplied by the debt to GDP ratio [Note: the primary balance is the difference between revenues and spending excluding interest payment on the debt].

With a simple formula: to maintain a stable debt-to-GDP ratio you need a primary surplus of

Let me look at some historical facts to understand the potential scenarios these countries are facing. After my previous post on Italy, let me look at Spain today, one of the countries that is also seeing spreads rapidly increasing.

The way we normally look at the question of solvency is by asking what type of effort the government needs to do to keep the debt under control. The typical benchmark is to look at the current ratio of government debt to GDP and think of scenarios where this ratio remains constant. In the case of Spain, this ratio is 60-67% measured in gross terms and 48-56% in net terms. The range corresponds to the number for 2010 and the forecast by the end of 2011. Let's just use 65% as the relevant ratio.

To keep this ratio constant, the Spanish government has to deliver a primary balance which is equal to the difference between the interest rate it pays on the debt (r) and the growth rate of GDP (g) multiplied by the debt to GDP ratio [Note: the primary balance is the difference between revenues and spending excluding interest payment on the debt].

With a simple formula: to maintain a stable debt-to-GDP ratio you need a primary surplus of

(r-g) Debt/GDP

Interest rates and growth rates have to be measured in the same units so we either measure them in nominal or real terms. Let me choose nominal rates.

Some facts: In the period 2000-2011, average nominal growth in Spain has been equal to 5.23% (out of which 2.17% was real growth). If we exclude the crisis years (2008-2001), average nominal growth was as high as 7.46%.

I am focusing at the post-Euro years as we want to avoid looking at a different monetary policy framework, but just for the sake of understanding history, in the previous decade (1988-99) Spain grew at a rate of 7.73 in nominal terms and 3.11 in real terms.

What about interest rates? Currently the Spanish government is paying about 4% on average (even if on the margin they are facing rates closer to 6%). If Spain managed to maintain rates at 4%, the required primary balance is

(4% - 5.23%) x 65% = -0.74%

So a deficit of 0.74% will do it. This does not look that different from actual numbers. Over the period 1999-2011, the government primary balance in Spain was -0.57%. If we exclude the years of the crisis and focus on the expansion 1999-2007, the primary balance was +2.24%, a significant surplus.

In other words, if Spain faced an interest rate of 4%, and even if within the next decade they experienced another massive crisis with four really bad years (as bad as 2008-2011) in terms of low growth and large deficits, the debt to GDP ratio would still remain at 65% ten years from now. "Business as usual" would do it. This is a very conservative scenario where we are asking no change in policies to the Spanish government.

Is 4% a reasonable interest rate? No if you look at markets today. But here is where the self-fulfilling nature of the crisis comes in. The relevant question to me is whether can we build a scenario for Spain that is conservative in terms of growth and fiscal efforts coupled with rates which are not too far to a risk-free rate, and where we feel that we can guarantee with almost 100% confidence that the debt will remain stable. If this scenario is possible, then the interest rate of 4% is justified because we are looking at a world of no default.

Of course, if we start with an interest rate of 15%, then all the calculations above will send you in the direction of default, which would justify the high interest rate we started with.

But if both scenarios seem plausible then we are facing multiple equilibria and we need to find a way to coordinate to the good one, the one without default. Looking at last week, it seems that we are going in the opposite direction. So it looks like the only way out is for all of us suddenly become optimistic, or the ECB steps in and helps us coordinate to the good equilibrium.

Antonio Fatás

Update: And Paul Krugman is also puzzled about interest rates in Euro countries when you compare them with fiscal policy outcomes in those countries. He cannot understand how interest rates for Austrian government debt remain so high giving its low debt, low unemployment and a current account surplus.

Antonio Fatás

Update: And Paul Krugman is also puzzled about interest rates in Euro countries when you compare them with fiscal policy outcomes in those countries. He cannot understand how interest rates for Austrian government debt remain so high giving its low debt, low unemployment and a current account surplus.

Wednesday, November 16, 2011

The not-so-original sin of finding others to pay for it.

Paul Krugman talks about the causes of the current sovereign default crisis in terms of what economists call "the original sin". The concept was developed to describe situations in which a country borrows in someone else's currency. When faced with a crisis, large devaluations of their exchange rates make the value of debt increase, which leads to default and possibly a deeper crisis. Krugman argues that a similar logic applies to Euro countries today: Italy has borrowed in a currency (Euro) that they do not control and this is a problem. If Italy had borrowed in their own currency they will always be a way out of a high debt situation: printing more Italian Liras.

Let me take a step back before I comment on how the "original sin" applies to Europe. What is a government default? Government debt is a result of spending decisions that have not been financed with tax revenues. If government debt is to be paid back it simply means that some future tax payers will pay for the spending done in previous years. If debt is not paid back and government defaults, it is simply a shift in the burden of paying for the debt from current and future tax payers to someone else (bond holders). In that sense, default of a government has nothing to do with default of a company where we tend to think about a failure of a business model. It is simply about finding someone else to pay for our spending, not tax payers.

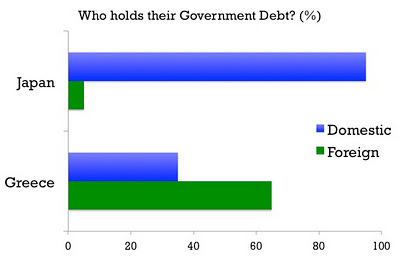

But who else will pay for it? In a closed economy (no international trade or capital flows, think about the world), it is not obvious to find "others" who will pay for our spending. You can shift the burden from tax payers to bond holders but in a closed economy both are citizens of your country, in some cases they are the same individuals. No economy is closed but some do not look far from this example. Below is a chart comparing Greece and Japan in terms of who holds their government debt (domestic versus foreign investors).

In the case of Japan, most of the Japanese government debt is held by Japanese citizens. If the government of Japan defaults it is equivalent to sending a tax bill to only bond holders. But they are Japanese tax payers so there is very little difference between default and taxes, there is no choice! I am, of course, simplifying what is a more complex situation: not every tax payer in Japan has an amount of government bonds which is proportional to their income and Japan is an open economy but to a large extent we are talking about a redistribution decision. The comparison to Greece is a good way to understand that the trade offs and consequences of a decision to default are not the same for Greece. Greece can potentially pass the burden to others (foreigners) who are currently holding its debt.

Back to the "original sin" discussion. When a government borrows in its own currency, there is a third alternative to taxes and default: printing money. Conceptually, it not different from the other two: you need to grab someone else's resources. Printing money leads to seignorage via inflation and this is an alternative source of income that can be seen as a tax on those whose assets are denominated in nominal terms. Some of these individuals are also tax payers, some are the ones who are currently holding your bonds, so you might be passing the bill to the same people but in different proportions (as in the Japanese example).

At the end of the day, default, taxes or seignorage are three ways to pay for the spending governments have already done. They are not that different conceptually. In a closed system there is no way to avoid grabbing resources from your own citizens - in some sense deciding between the three choices is simply a redistribution decision. In an open economy you might be able to grab resources from other countries by defaulting on debt held by foreigners. Although conceptually similar, each of the three methods differ in terms of the political consequences or even feasibility. Passing the bill to foreigners will tend to be easier from a political point of view although it will have more damaging effects in terms of credibility. In some countries raising taxes is more feasible than creating inflation. In other cases it will be the other way around. From an economic point of view it might be that the same individuals end up paying the bill but sending them a bill in a different format or color just happens to be easier.

Antonio Fatás

Let me take a step back before I comment on how the "original sin" applies to Europe. What is a government default? Government debt is a result of spending decisions that have not been financed with tax revenues. If government debt is to be paid back it simply means that some future tax payers will pay for the spending done in previous years. If debt is not paid back and government defaults, it is simply a shift in the burden of paying for the debt from current and future tax payers to someone else (bond holders). In that sense, default of a government has nothing to do with default of a company where we tend to think about a failure of a business model. It is simply about finding someone else to pay for our spending, not tax payers.

But who else will pay for it? In a closed economy (no international trade or capital flows, think about the world), it is not obvious to find "others" who will pay for our spending. You can shift the burden from tax payers to bond holders but in a closed economy both are citizens of your country, in some cases they are the same individuals. No economy is closed but some do not look far from this example. Below is a chart comparing Greece and Japan in terms of who holds their government debt (domestic versus foreign investors).

In the case of Japan, most of the Japanese government debt is held by Japanese citizens. If the government of Japan defaults it is equivalent to sending a tax bill to only bond holders. But they are Japanese tax payers so there is very little difference between default and taxes, there is no choice! I am, of course, simplifying what is a more complex situation: not every tax payer in Japan has an amount of government bonds which is proportional to their income and Japan is an open economy but to a large extent we are talking about a redistribution decision. The comparison to Greece is a good way to understand that the trade offs and consequences of a decision to default are not the same for Greece. Greece can potentially pass the burden to others (foreigners) who are currently holding its debt.

Back to the "original sin" discussion. When a government borrows in its own currency, there is a third alternative to taxes and default: printing money. Conceptually, it not different from the other two: you need to grab someone else's resources. Printing money leads to seignorage via inflation and this is an alternative source of income that can be seen as a tax on those whose assets are denominated in nominal terms. Some of these individuals are also tax payers, some are the ones who are currently holding your bonds, so you might be passing the bill to the same people but in different proportions (as in the Japanese example).

At the end of the day, default, taxes or seignorage are three ways to pay for the spending governments have already done. They are not that different conceptually. In a closed system there is no way to avoid grabbing resources from your own citizens - in some sense deciding between the three choices is simply a redistribution decision. In an open economy you might be able to grab resources from other countries by defaulting on debt held by foreigners. Although conceptually similar, each of the three methods differ in terms of the political consequences or even feasibility. Passing the bill to foreigners will tend to be easier from a political point of view although it will have more damaging effects in terms of credibility. In some countries raising taxes is more feasible than creating inflation. In other cases it will be the other way around. From an economic point of view it might be that the same individuals end up paying the bill but sending them a bill in a different format or color just happens to be easier.

Antonio Fatás

Monday, November 14, 2011

Italy: not good but we have seen this before

It is hard to find much optimism by looking at the Italian economy today: Low growth, high government debt, limited confidence of financial markets and no government. Pick a random newspaper or economics blog today and the tone will be on a range from mildly pessimistic to catastrophic. I will not repeat their arguments and instead I will do my best to be a contrarian and argue that maybe it is not as bad as it looks. Or maybe it is, but Italy has managed to live with such a bad situation for years so there is some hope. This might not be enough to turn you into an optimistic but at least it provides a perspective to how similar episodes ended.

When we look at gross debt we see that Italy is now back to where it was in 1994. If we focus on net debt the current level of debt is significantly below what it was in 1994. So Italy has seen similar or higher levels of debt before.

We can then argue that those times were different, that Italy had its own currency (although it was heading towards the Euro) and that a combination of high inflation and fast growth allowed them to stabilize that high level of debt.

Certainly it was not growth what saved them. GDP growth in Italy has been low during this period of time: the average growth rate for the period 1994-2007 was 1.6%, clearly below the growth in other Euro countries (France grew at 2.6% and Spain at 3.6% during the same period of time).

What about interest rates? Maybe the government of Italy did not face the high interest rates that they face today? Below is a chart of the 10-year interest rate for Italian government bonds.

Here is what I learn from the previous three charts. To my surprise, and the surprise of many, Italy has managed to sustain a very high level of debt even when facing high interest rates by generating large enough primary surpluses. And it has done so with a political environment that has been volatile and in some cases driven by very poor choices. Does it mean that they can keep going like this forever? No, there might be a sense of fatigue and maybe the end of what it looks like an unstable model. But, at the same time, it is interesting to see when we look back at history that a similar episode did not automatically lead to default even with poor economic policy choices. And if you want to be even more optimistic, there is some hope that this crisis is not wasted and the future Italian government finds an even better way to manage a very difficult situation.

Antonio Fatás

Below is the Italian government debt expressed as % of GDP. There are two lines, the gross and net values of government debt. Net debt is a more appropriate measure as it takes into account some of the financial assets that the Italian government owns and it is equivalent to what is referred to in the US as "government debt held by the public". I include gross debt as well because the "net" measure is noisy and some times unreliable so some prefer to focus on gross debt.

When we look at gross debt we see that Italy is now back to where it was in 1994. If we focus on net debt the current level of debt is significantly below what it was in 1994. So Italy has seen similar or higher levels of debt before.

We can then argue that those times were different, that Italy had its own currency (although it was heading towards the Euro) and that a combination of high inflation and fast growth allowed them to stabilize that high level of debt.

Certainly it was not growth what saved them. GDP growth in Italy has been low during this period of time: the average growth rate for the period 1994-2007 was 1.6%, clearly below the growth in other Euro countries (France grew at 2.6% and Spain at 3.6% during the same period of time).

What about interest rates? Maybe the government of Italy did not face the high interest rates that they face today? Below is a chart of the 10-year interest rate for Italian government bonds.

As it is clear from the chart, financial conditions back in 1994-1995 were extremely difficult for the Italian government with nominal interest rates as high as 12%. Much higher than the current levels of 6-7% that look as unsustainable. Of course, what matters is not nominal rates but real rates (what really matters is the difference between interest rates and growth but I do not have that chart ready in my computer). Below is a chart with real rates that confirms that interest rates today remain low compared to the ones faced by Italy in 1994-95.

Here is what I learn from the previous three charts. To my surprise, and the surprise of many, Italy has managed to sustain a very high level of debt even when facing high interest rates by generating large enough primary surpluses. And it has done so with a political environment that has been volatile and in some cases driven by very poor choices. Does it mean that they can keep going like this forever? No, there might be a sense of fatigue and maybe the end of what it looks like an unstable model. But, at the same time, it is interesting to see when we look back at history that a similar episode did not automatically lead to default even with poor economic policy choices. And if you want to be even more optimistic, there is some hope that this crisis is not wasted and the future Italian government finds an even better way to manage a very difficult situation.

Antonio Fatás

Friday, November 11, 2011

Europe versus the US: Fight!

Comparing economic performance in Europe and the US is always interesting and in some cases controversial, especially when politics enters the debate. European politicians blamed the US for causing the 2008-09 crisis and now it is the turn of the US politicians to blame the Europeans for their inability to handle the sovereign crisis.

Jeff Frankel has a nice blog entry comparing the performance of Europe and the US today under the title "Who is screwing up more: Europe or the US?". Not easy to make that call.

Some of the European economic problems come from the bad performance of politicians. Given that Italy is at the center of the crisis today, one wonders how a former G7 member and an economy of around 2 trillion dollars has been under the direction of Silvio Berlusconi for so many years...

But given that this post is about the competition between Europe and the US, we can check how some of the large US states (similar in size to Italy) compare in this respect: California (about 2 trillion dollars) has been led by Arnold Schwarzenegger for years; and the current governor of Texas (an economy of about 1.3 trillion dollars) is Rick Perry - the one who cannot remember the three government agencies that he plans to close if he becomes president. In case you have not seen the video, here it is:

But there is hope: Berlusconi is on his way out and it looks as if Rick Perry will not be the next US president.

Antonio Fatás

Jeff Frankel has a nice blog entry comparing the performance of Europe and the US today under the title "Who is screwing up more: Europe or the US?". Not easy to make that call.

Some of the European economic problems come from the bad performance of politicians. Given that Italy is at the center of the crisis today, one wonders how a former G7 member and an economy of around 2 trillion dollars has been under the direction of Silvio Berlusconi for so many years...

But given that this post is about the competition between Europe and the US, we can check how some of the large US states (similar in size to Italy) compare in this respect: California (about 2 trillion dollars) has been led by Arnold Schwarzenegger for years; and the current governor of Texas (an economy of about 1.3 trillion dollars) is Rick Perry - the one who cannot remember the three government agencies that he plans to close if he becomes president. In case you have not seen the video, here it is:

But there is hope: Berlusconi is on his way out and it looks as if Rick Perry will not be the next US president.

Antonio Fatás

Wednesday, November 9, 2011

Plan B for Europe: Do not Stare Into the Abyss.

Everyone is running out of hope regarding a solution for the economic problems in Europe. A change in government in Greece, the possibility of Berlusconi stepping down are not enough to bring confidence to markets or the public. In the Econ Blogosphere we only see increasing pessimism: Mark Thoma, Barry Eichengreen, Paul Krugman, and many others.

Tim Duy makes the point that so far stock markets, in particular, Wall Street is ignoring the risks that are building in Europe. He draws an analogy to what was going on in 2007 when stock markets were still booming and ignoring the fact that we were literally looking into the abyss but we could not see it. He believes that today Europe is unable to see the abyss ahead of them and Wall Street is ignoring the problem assuming that it will not hit the US.

But what does the abyss looked like in 2007? In 2007 we had built a set of imbalances on asset prices, in particular housing prices that had supported a different imbalance, on spending and debt (private and or public). While some did not want to see the abyss, those who saw it were looking into a fall in asset prices, financial disruption and a sharp fall in economic activity.

What does the abyss look like today for Europe? We know with certainty that there will be partial default in Greece, but as I have argued before this does not qualify as an abyss (for Europe). It is a bump on the road, maybe a big one but not large enough to justify a deep recession in the Euro area. The fear is about others following, in particular Italy and Spain. But here is where the 2011 abyss looks very different from the 2007 one: this time the crisis is much more linked to confidence. In 2007 the adjustment in asset prices was unavoidable. Today, we debate about whether the Italian government or the Spanish government are solvent and the answer is much less clear. Why? Because solvency depends on confidence and confidence depends on how we see solvency. If Italy keep losing the confidence of markets, as it is happening today, then they are insolvent, too big to fail but too big to be rescued.

So if we keep staring at the abyss, we are just making it deeper. And the deeper the abyss is, the more we want to stare into it.

So the solution is to stop staring into the abyss. Given where we are today there is only one way to do that, to have the ECB taking a very aggressive stance on how they are willing to support the governments of Italy or Spain if their interest rates keep increasing. Communication from European governments, over stretching the EFSF is not going to be enough anymore, you need the ECB to stand between us and the abyss so that we stop staring into it.

Antonio Fatás

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

It is not Greece, it is Fear.

I made this point before when I discussed the exposure of a French bank (Societe Generale) to Greek debt in comparison to other losses such as the loss that a single trader (Jerome Kerviel) caused to that bank back in January 2008.

Today I see that Societe Generale released the results of the third quarter of 2011 and that comparison has become even more interesting. In a balance sheet of about EUR 650 bn, exposure to Greek government debt is as low as EUR 575m. Exposure to the government debt of Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Greece and Italy combined is "only" EUR 3.4bn. This combined amount remains below the loss caused by Kerviel back in 2008 (about EUR 4.9 bn).

(Note: there is nothing specific about Societe Generale in this analysis. I just picked it up as an example of a large French bank. I assume that others look similar.)

Antonio Fatás

Today I see that Societe Generale released the results of the third quarter of 2011 and that comparison has become even more interesting. In a balance sheet of about EUR 650 bn, exposure to Greek government debt is as low as EUR 575m. Exposure to the government debt of Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Greece and Italy combined is "only" EUR 3.4bn. This combined amount remains below the loss caused by Kerviel back in 2008 (about EUR 4.9 bn).

(Note: there is nothing specific about Societe Generale in this analysis. I just picked it up as an example of a large French bank. I assume that others look similar.)

Antonio Fatás

Tuesday, November 1, 2011

Politics: the beginning and the end of the Euro

As much as economists have been wondering for years about the economic benefits and costs of sharing a currency, such as the Euro, the decision to create the Euro area and to be one of its members has always been a political one. As an academic, I have written about the costs and benefits of sharing a currency and my work has led me to the belief that, in the case of the Euro, the benefits outweigh the costs. When I have had an occasion to present my work in this area to those in charge of making the decision (politicians) I always realized that economic arguments matter very little when there are political constraints.

As an anecdote, back in January 2010 I wrote a chapter for a book about the 10 year anniversary of the Euro and the lessons for countries such as Sweden that stayed out of the Euro area. Anders Borg (Swedish Finance Minister) was in charge of commenting on our book and he made it very clear that from the point of view of economics there was no doubt that Sweden belongs in the Euro area but that we need to wait for the "right timing" (a similar position, although less explicit, is held by the UK government with their entry tests). And the right timing is decided on political grounds and not so much on economics. Given the current Euro crisis, it is likely that the timing of entry of any of these countries has just moved into the very distant future...

The countries that are part of the Euro area joined under different political agendas. There is the core (France, Germany) who has been driving European integration through the years (for reasons linked to the end of WWII). There is the periphery (Greece, Spain) who wanted to be like the core. With relatively low income per capita, their societies aspired to converge not only in terms of development but also from an institutional point of view to the levels of the rich Euro partners. And this was the reason why these countries supported every step of European integration, including membership to the Euro area.

And now are looking at the possibility of exit. In the last months, when I have been asked whether Euro exit was a possibility I have always said that it would be economic suicide for any country to leave the Euro area. But economic and political incentives are not always aligned and I have also argued that I could imagine a country leaving the Euro area if the political dynamics of the country produce a potential referendum where the question of Euro membership is simply read as "us versus them". In that environment you could imagine a country leaving the Euro area simply because its citizens have lost faith in the European project and the other countries are seen as enemies not allies. This has happened in recent times in Europe, where a referendum (about the Maastricht Treaty or the European constitution) was turned down in several countries and the only thing the European politicians could do is to repeat the referendum over and over again until it was approved...

Today the Greek government has surprised other Euro members and financial markets announcing a referendum on the last Euro bailout plan. This can be the end of the Euro, at least in some countries. Given the difficult economic situation in Greece and Europe, a "No" vote is not just possible but very likely. And while the vote will be just on the details of the plan, it will be seen as a referendum on the Euro. And this time there will be no second chance to repeat the vote if we do not like the outcome. And my fear is that just the announcement of a vote and the anticipation of that scenario might lead to a crisis months before the referendum takes place.

Antonio Fatás

As an anecdote, back in January 2010 I wrote a chapter for a book about the 10 year anniversary of the Euro and the lessons for countries such as Sweden that stayed out of the Euro area. Anders Borg (Swedish Finance Minister) was in charge of commenting on our book and he made it very clear that from the point of view of economics there was no doubt that Sweden belongs in the Euro area but that we need to wait for the "right timing" (a similar position, although less explicit, is held by the UK government with their entry tests). And the right timing is decided on political grounds and not so much on economics. Given the current Euro crisis, it is likely that the timing of entry of any of these countries has just moved into the very distant future...

The countries that are part of the Euro area joined under different political agendas. There is the core (France, Germany) who has been driving European integration through the years (for reasons linked to the end of WWII). There is the periphery (Greece, Spain) who wanted to be like the core. With relatively low income per capita, their societies aspired to converge not only in terms of development but also from an institutional point of view to the levels of the rich Euro partners. And this was the reason why these countries supported every step of European integration, including membership to the Euro area.

And now are looking at the possibility of exit. In the last months, when I have been asked whether Euro exit was a possibility I have always said that it would be economic suicide for any country to leave the Euro area. But economic and political incentives are not always aligned and I have also argued that I could imagine a country leaving the Euro area if the political dynamics of the country produce a potential referendum where the question of Euro membership is simply read as "us versus them". In that environment you could imagine a country leaving the Euro area simply because its citizens have lost faith in the European project and the other countries are seen as enemies not allies. This has happened in recent times in Europe, where a referendum (about the Maastricht Treaty or the European constitution) was turned down in several countries and the only thing the European politicians could do is to repeat the referendum over and over again until it was approved...

Today the Greek government has surprised other Euro members and financial markets announcing a referendum on the last Euro bailout plan. This can be the end of the Euro, at least in some countries. Given the difficult economic situation in Greece and Europe, a "No" vote is not just possible but very likely. And while the vote will be just on the details of the plan, it will be seen as a referendum on the Euro. And this time there will be no second chance to repeat the vote if we do not like the outcome. And my fear is that just the announcement of a vote and the anticipation of that scenario might lead to a crisis months before the referendum takes place.

Antonio Fatás

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)