The BIS just published its

annual report (and some of its arguments are also presented in a lecture that

Raghuram Rajan gave at the BIS at the time of the launch). Paul Krugman has posted a

reaction to the report where he expresses surprise at how the report seems to ignore evidence we have accumulated during the crisis. I will not repeat Krugman's arguments here but instead focus on what I perceive to be a series of inconsistencies in the arguments used in the BIS report - inconsistencies that are also present in the lecture by Rajan.

Both the BIS report and the speech by Rajan present a critical view of the fiscal and monetary policy stimulus we have witnessed over the last years. It is a soft criticism as they seem to agree that some of it was needed, but then they present arguments that suggest that both policies have gone too far, are not being effective, they might be slowing down growth and they will be a source of uncertainty going forward. The criticism is not always accompanied with an alternative. There is a recognition that this is a crisis caused by low demand but at some point the arguments is turned around to argue that more demand might not be a solution (given all the structural problems we have).

The report is long so let me focus on two issues where I feel their arguments are not only not supported by the evidence but also lack some internal consistency.

The report in unclear about whether the short-run and long-run recipes to get out of the crisis should be different. Everyone understands that some of the trends that we witnessed before the crisis were unsustainable from a long-run point of view. Some of the spending patterns of the private sector (and the public sector in some cases) were leading to an accumulation of debt that needed a correction. No disagreement here. But when the adjustment took place it did it in a way which was not efficient. A deep recession started (and the BIS report explains very clearly why lack of demand created this recession).

How do you deal with a recession that is defined as a period where output is below its trend? Even if we agree that the trend is not growing as fast as before (although I am not sure we have enough evidence to prove this but I am open to the argument), isn't it obvious that we are producing below trend? And if we are, what we need are policies that restore full employment, that bring output close to equilibrium. These are the policies that can increase output in the short run. Supply (structural) policies can be a source of output in the long run and there might be great benefits to those policies as well, but unless one is willing to argue that output today is at potential, there must be room for demand policies. The BIS does not take a clear stance on this. It simply criticizes those who argue in favor of additional stimulus on the basis that they ignore structural problems. But this is not correct. Those of us who have argued in favor of demand policies have never denied that there is room for structural reform in many advanced economies. It is a matter of timing.

And what about the evidence? The argument from Rajan that "what is true is that we have had plenty of stimulus." is at odds with the evidence. Both fiscal policy and monetary policy have been less expansionary (or more contractionary) than in any previous recession.

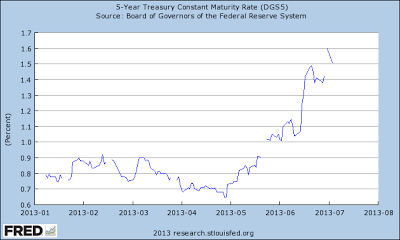

When it comes to monetary policy the report adopts a similar attitude: while it admits that many of the policies were necessary there is a criticism that central banks have gone too far and now they are going to cause trouble as they clean up the mess that they made. Let me focus on one of the arguments they make: that central banks has been too accommodative and that interest rates have been too low. The report makes the argument that this has been going one for years now.

Below is a chart from section VI.6 of the BIS report to show that interest rates are too low today and they have been low for most of the years since 2000, both in advanced economies and emerging markets.

The chart uses the Taylor rule as a benchmark for what constitutes appropriate interest rates. The Taylor rule was proposed by John Taylor in 1993 to describe the behavior of the US Federal Reserve during the 80s. The tool became very popular because it could explain interest rates just by using two variables: inflation and the output gap. Anyone who has studies Taylor rules knows that the moment you apply it to a different period or a different country, the rule does not work as well. There are many problems: which is the appropriate measure of the output gap or inflation, are the coefficients changing over time, during recessions, etc.

But the fundamental issue with the Taylor rule is about the appropriate benchmark for the real interest rates in normal times. The original Taylor rule used the value 2% as the "natural" real interest rate. This number worked well because it was coming from the data that Taylor was looking at (in some sense Taylor estimated this number using data from the 80s in the US). But this is an equilibrium concept and as such it can change. What we teach our students is that this rate is determined by the balance between Saving and Investment. What we know is that since the end of the 90s some countries started saving at much higher rates than before, what Ben Bernanke called the Saving Glut back in 2005. What we also know is that the global recession has pushed Saving higher in depressed economies and that we have seen limited reason to invest (e.g. the anecdotal reference to companies sitting in a pile of cash not wanting to invest). In that environment, we expect the equilibrium real interest rate to go down significantly. The BIS report and Rajan's speech keep referring to the "Keynesian" view that equilibrium real interest rates have turned negative. What is "Keynesian" about that view? The Saving / Investment imbalance is an equilibrium concept that is present in any economic model I know. The BIS report takes no stance in this debate, it simply criticizes others. What is the real equilibrium interest rate in the world economy today according to the BIS? 2%?

Finally, if it is true that monetary policy has been so accommodative for about 13 years, where is inflation? The Taylor rule was partly proposed as a benchmark on how to maintain a stable rate of inflation. If we keep the interest rate below what is appropriate for 13 years we should see massive inflation everywhere in the world. But there is no inflation. Isn't this enough evidence to stop the BIS from producing the chart above as a proof that central banks have gone too far?

Yet another day when one feels that this crisis has been a wasted crisis for economists to learn about our mistakes.

Antonio Fatás